Will Eisner’s Life, Drawn by His Own Hand

Autobiography

Life, in Pictures: Autobiographical Stories

By Will Eisner, with an introduction by Scott McCloud

W.W. Norton & Company, 496 pages, $29.95.

In one of many ironies whose origins may be suggested here, artist-entrepreneur Will Eisner died in 2005, just as his collected oeuvre had begun to persuade readers that he was a true master and not a historical footnote to the otherwise juvenile art form known as the comic book. His most thoughtful works have posthumously appeared — or reappeared more prominently than in their original form — and a documentary about his life premiered last month. That is to say, he lived almost long enough to see a life’s work vindicated.

“Life, in Pictures,” may be the one book that he would have most wished to see in print. A collection made up of three principal parts plus outtakes and annotations, it is as close as we will ever get to his own story in comics. Each of the three — “The Dreamer,” “To the Heart of the Storm” and “The Name of the Game” — is itself complete. Together they also make up an inner saga of Golden Age comic art.

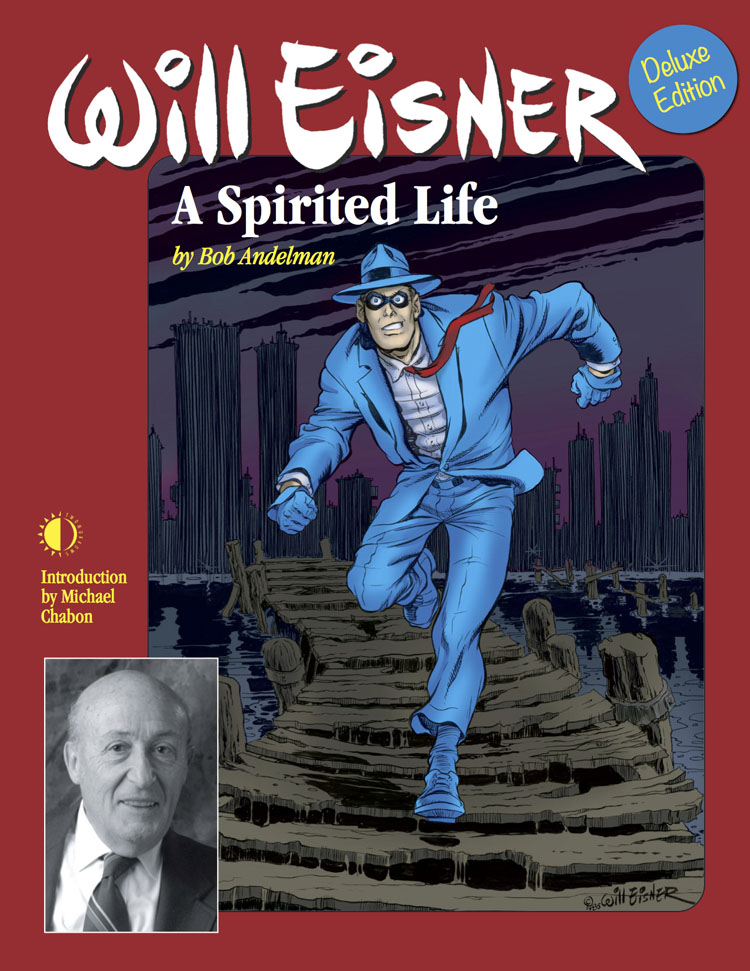

An editor’s note by former alternative comics publisher Denis Kitchen explains carefully that Eisner, one of the founders of the comic book trade at the end of the 1930s, resurfaced thanks to the influences of the ’60s generation. In “The Spirit,” his syndicated strip of the 1940s, Eisner pushed the envelope formally, establishing a cinematic look to a genre detective character and cast. The underground comix revealed to him that the previous limits on sex and other topics had been practically abolished, at least in certain venues. The artist could now do anything, even write and draw about the intimate details of personal life. So here, in Eisner’s later work when “The Spirit” had become a dim memory and the artist began to portray himself with the thinnest of disguises, we find Eisner, the Bronx boy, and his family drama, his determination to become an artist and his success at the suddenly evolving and suddenly much more Jewish comics trade. Kitchen follows the narratives with almost compulsive annotations of scenes and characters. No nonfiction volume, it is safe to say, has ever told the back story of comic books more closely.

For my money, the best parts are “The Dreamer” and “To the Heart of the Storm,” intertwined sagas of the boy’s aspirations and his intimate glimpses back at his family life while on a troop train during the Good War. We see father, a would-be artist in Vienna, repeatedly stopped short by endemic antisemitism; in the new world, for father and son, the experience is more episodic but hardly less painful for that. They are never far, even with seeming pals or associates, from the crude stereotypes and stinging generalizations that were “normal” in pre-Holocaust America and not so absent for years after. Eisner’s father thus slipped to failure from success repeatedly in the garment trade, his ever-troubled mother had children too often and the whole family trauma comes more vividly clear to the artist in retrospect. The emerging world of comic-book production does not look so different from the garment trade after all: full of misery, hustlers and failures. The determined lad drives himself forward, an artistic and business success, but with the shadow of his father’s life never far behind.