(NOTE: The following is an excerpt from the only authorized Will Eisner biography, Will Eisner: A Spirited Life by Bob Andelman. I am sharing it today as a little-known Stan Lee story on the day we learned of his passing, November 12, 2018. I hope you will enjoy it. — Bob Andelman)

Stan Lee called Will Eisner twenty years after production ceased on The Spirit and Eisner had turned his back on the comic book industry.

The creator or co-creator of every major Marvel Comics character from Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four to the X-Men and the Hulk, Lee—born Stanley Lieber, himself a graduate of Eisner’s alma mater, DeWitt Clinton High School—was editor and publisher of the Marvel line in 1972. Lee, in fact, had over- seen Marvel—a company started and run for decades by his uncle and boss, Martin Goodman—since his teenage days in the1940s. Every modern Marvel comic book began with the line“Stan Lee Presents.” He was the first brand name talent in the maturing business. But after more than a decade of incredible growth and fame, Lee was ready to move on. He wanted Eisner to replace him at Marvel so he could go to Hollywood and make movies.

Lee felt that Eisner might be the only comic artist around who had the respect of cartoonists and who also had the business expe- rience to manage an enterprise of Marvel’s size and scope.

When Lee rang in the 1970s, Eisner figured it was a social call.Eisner had been out of comic books for twenty years. Comic book conventions were still a relatively new phenomenon, and the direct sale comic book market was still a few years off. Eisner, recently separated from PS, was not yet a “revered legend”—more like an old-timer with a portfolio.

“I hear you are at liberty,” Lee said.

Eisner laughed. They chatted for a minute or two. Eisner still didn’t know what was coming.

“Why don’t you come down to my office at Marvel,” Lee said. “I would like to talk with you about something.”

So Eisner went. When he arrived, Lee didn’t mince any more words. “To tell you the truth,” he said, “I need somebody to replace me here. I want to go to Hollywood. I love the Hollywood scene. This isn’t for me any more. But they won’t let me go unless I can find a suitable replacement.”

Eisner was pretty stunned that that was why Lee wanted to see him, thinking originally that perhaps Lee wanted him to do a book for Marvel. Many artists from the Golden Age of Comics were turn- ing up for a last hurrah at Marvel, DC, or Charlton, and Eisner figured that Stan opened his Rolodex and his wandering finger landed on “E.” Eisner remembered Lee being surprised to learn when they met years earlier that Eisner wrote all the Spirit stories. Lee said he had been impressed that Eisner could write and draw.

“You have business experience,” Lee said. “You’d be ideal for this job.”

During the course of the conversation, Lee’s boss from Marvel’s then-corporate parent joined them. The meeting quickly became a job interview. He wanted to know what Eisner thought about comics, where he thought the industry was going, and what he would do about it.

“Well,” Eisner said, “one of the first things I would do is abandon the work-for-hire system that you have here.”

There was a noticeable evacuation of air in the room.

Lee winced.

“Oh, we can’t do that,” Lee’s boss said. “That’s impossible to do here.”

“I don’t see why,” Eisner said. “First of all, allow the writers and artists to keep copyrights. The book publishing business does that and does it quite profitably. Then return their original art to them.You asked me what I would do in my role here; that’s what I woulddo right away.”

Other comic book artists that Eisner knew sustained a certainamount of animosity toward Lee. Jack Kirby, for example, alwaysmaintained that he brought the idea for Spider-Man to Stan. Until the Spider-Man movie debuted in 2002, Lee generally took sole credit. The movie credited the character’s creation to Stan Lee and artist Steve Ditko.

“Stan wasn’t terribly popular among other artists, either,” Eisner said later. “He was regarded by and large as an exploiter, which is the fate of all publishers. Creators will always regard publishers as exploiters. I guess it is something that psychiatrists can discussbetter, but I have always regarded it as a child/parent relationship.Artists need somebody to hate. In the comic field, the publishers are close at hand.”

After more idle chat between Lee and Eisner, it became clear that Marvel was unprepared for Eisner’s independent-artist approach to corporate policy. It’s understandable that the company was star- tled by Eisner’s ideas; there wasn’t yet a large comic book indus- try press, so his views were still pretty revolutionary. In any event, Eisner could see where the conversation was going. Finally he said, “Gentlemen, I don’t think this is for me.”

Lee walked Eisner out to the elevator. He tried one more time.“C’mon, Will,” he said, “Why not?”

“Stan,” Eisner said, “this is a suicide mission.”

“The pay is good,” Lee said in desperation.

“I understand that,” Eisner said. “But money is not what I am interested in right now. I have money.”

The idea of working for Marvel was not attractive to Eisner, but not because it was Marvel. The idea of working for any large corporation again after the Koster-Dana fiasco was unattractive.

“I never had the outlook necessary for the mainstream comic book market,” Eisner said. “I could never do superheroes well. My heroes always looked like they were made of styrene foam. The Spirit evinced psychological problems. Spider-Man did, too, of course. Stan once told me that he ‘liked the idea that the Spirit was human and not quite superhero-ish.’”

Lee’s memory of meeting with Eisner was hazy at best, but he didn’t doubt Eisner’s account. “Will certainly would have been a good choice for me to want to run the place if I were not there any more,” he said.

When Eisner laid out his conditions, Lee knew they would never be accepted by the corporate bosses.

“At that time, that wasn’t the way it was done in comics,” Lee said. “I am sure that whoever was the publisher then wouldn’t have been willing to go along with that. But it would have been fine with me. I just wanted Will to be part of Marvel. I wanted in some way to have an association with him, because I certainly would have thought that he would be a great asset to us. You can quote me on that. Unfortunately, I had nothing to do with the business arrangements. I would have said to whoever the hell handled the business, ‘I want to hire this guy,’ or ‘I would love this guy to work with us,’ but then he would have had to talk to the business department and make the deal, because I was never part of that.

“I wasn’t a big reader of The Spirit,” Lee added, “because it was never in a newspaper that I read. I was in New York, and as far as I know, it wasn’t in New York, but I had heard about it and I hadseen bits and pieces of it here and there, and I was always incred- ibly impressed with the artwork, with the layouts, mainly with the first page, with the opening page. Each title was done differently on each weekly episode where the title ‘The Spirit’ was really part of the artwork. And that impressed the hell out of me. I thought that Will was a really fine designer.

“He is really one of the only creative people in the business who was also a businessman who was able to make money at it and was smart enough to own everything he did. And I have always admired him for that.”

Writer and former Marvel Editor in Chief Marv Wolfman, who joined Marvel Comics in 1972, clearly remembered Lee’s interest in hiring Eisner.

“Stan was a huge fan of Eisner’s work,” Wolfman said. “I remember him talking about getting in touch with Eisner to head up something.”

Roy Thomas, longtime Marvel Comics writer and editor in chieffrom 1971 to 1980, also knew that Lee reached out to Eisner. “I have a memory of it,” he said. “I suspect it was between 1972 and 1974.”

If Eisner took the job, it would have caused many more changes.

“It would have hastened my departure to DC by about ten years,” Thomas said. “I don’t think I could have worked for Will.” As for Marvel Comics publishing The Spirit, Thomas doesn’t think that would have worked for anyone.

“The things Will Eisner did had a lot in common with Stan,” Thomas said. “But if Stan were to do The Spirit, it would have been more like a Marvel Comic, and then it wouldn’t be The Spirit.”

When Eisner said no, Lee made a run at Harvey Kurtzman. He turned the job down, too.

Artist Batton Lash well remembered the week that Stan Lee offered Eisner his job at Marvel Comics. Lash was a student inEisner’s first cartooning class at New York City’s School of VisualArts. Eisner didn’t make a big deal of the Marvel proposal, Lash recalled. Eisner would often tell his students to pull their chairs up close and he would talk about a variety of subjects.

On this particular day, Eisner told a more memorable tale.

“Superheroes aren’t selling,” he said. “Even Stan Lee is losing interest. He called me the other day and asked if I wanted his job while he goes out to make movies.”

Being matter-of-fact about passing on the biggest job in comics was typical Eisner.

“I don’t think Will ever regretted turning Stan Lee down,” Lash said. “But I get the impression Stan was flabbergasted.”

Conversely, Eisner didn’t tell his students that Jim Warren was about to begin reprinting the Spirit stories from the 1940s; they discovered it on the newsstands like everyone else.

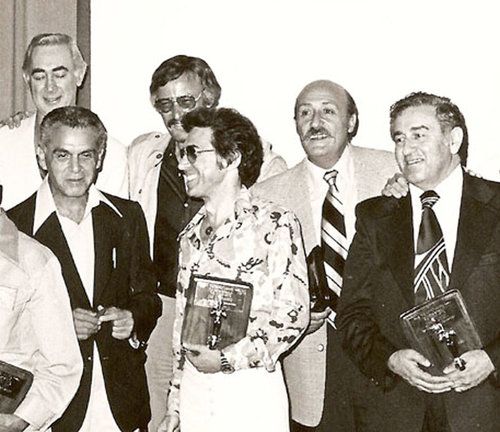

Lee and Eisner maintained a cordial, often joke-driven relationship based on mutual respect and one-upsmanship—a trait only Lee brought out in Eisner. They would often meet at conventions. “My wife claims that we are like two vaudeville comedians fighting each other for center stage,” Eisner said. “Apparently, Stan brings out a great deal of competitiveness in me.”

•••

Even before approaching Eisner about running Marvel, Stan Lee wanted to put out a magazine that would compete with Mad, Cracked, and Sick. He thought there might be room for a humor publication with Marvel Comics’ wit.

Lee told Roy Thomas that he wanted Eisner to create and run the magazine. “I think he was thinking of the National Lampoon, which was a hit,” Thomas recalled. “But Stan didn’t want to go as raunchy.”

Thomas went to lunch with Eisner as a follow-up to Lee’s interest in a magazine with the working title Bedlam. “I don’t remember much, but we talked about whatever Stan wanted,” Thomas said. “Eisner and I kicked around some ideas. I remember seeing some sketches that Will may have done.” Eisner even sent out a letter dated February20, 1973, to several artists’ and writers’ agents soliciting their interest. It read:

Dear Sir,

I have been engaged by Stan Lee and Marvel Comics Group to help them launch a new slick paper satirical magazine. Of course, since I am aware that you handle many talented profes- sionals who I believe have something worthwhile to say, I am writing to you to find out whether any of your clients would be interested in accepting an assignment or making submissions for our landmark premier issue and hope- fully beyond.

Will Eisner

Marv Wolfman said that he and fellow writer Len Wein—co-creator of the characters Swamp Thing and Wolverine—both then around twenty years old, received a telephone invitation from Eisner to come by and talk about working with him on a possible new humor magazine.

“I knew what The Spirit was, but this was before the Kitchen Sink and Warren reprints and it had not taken hold of fandom at that point,” Wolfman said.

When they arrived at Eisner’s Park Avenue office, the duo was greeted warmly and they listened to Eisner’s pitch. He gave them some background on his work, discussing The Spirit, PS, and other publishing projects.

“He was talking about doing a humor magazine of the National Lampoon variety. A lot of college humor,” Wolfman recalled.

The conversation lasted several hours. When it was over, both sides were disappointed.

“As much as we would desperately like to work with you, Mr. Eisner, it’s not right,” Wolfman said. “It won’t work.”

Eisner was puzzled.

“To do a college humor magazine today would mean an incred- ible amount of anti-government, anti-establishment material. Don’t you think that would conflict with your Army contract to produce PS?” Wolfman asked.

Eisner honestly hadn’t thought about that. And he conceded the logic—and smart business sense—in their decision to pass on the work.

“It really hurt us,” Wolfman said. “We would have loved to work with him. It would have helped so much. That was a bittersweet meeting. We could have learned a lot about the industry—a lot sooner—instead of picking up bits and pieces over the next few years.”

Wolfman and Wein didn’t walk away empty-handed, however; Eisner did sketches of The Spirit for each writer.

“Later on, when I was doing Crazy for Marvel, we licensed some of Will’s material from his Gleeful Guides series that fit in,” Wolfman said. “I always loved his work; Stan loved his work.”

Meanwhile, when Thomas reported back to Lee, he found his boss had cooled on Eisner for the project. And while Eisner produced several humorous, satirical books, it’s not surprising that he might not be the right person to guide a college humor magazine.

“Stan felt it wasn’t quite the direction he wanted to go. They weren’t on the same wavelength,” Thomas said. “This was during Nixon. It would have been difficult.”

After Eisner passed on Bedlam, Lee also talked with Harvey Kurtzman about the project. Kurtzman—the master of the genre who created Mad—dropped into Gil Kane’s office at Marvel, told his friend why he was there, and shook his head.

“Oh God,” Kurtzman said, “am I back to this?”

Kurtzman passed.

Lee eventually got his magazine together and called it Crazy.

Ironically, he offered the editor’s job to Denis Kitchen, who also declined. Crazy lasted from 1973 through 1983.

•••

One more “What If…” story about Eisner and Marvel:

Shortly after Jim Shooter became editor in chief of Marvel in January 1978, he and Eisner met for lunch at the Princeton Club. Shooter, who had recently agreed to begin producing an annual series of character crossover comics with DC, asked if Eisner would be interested in doing a one-shot Spider-Man vs. The Spirit. No character had ever crossed over into the Spirit’s world before.

“I don’t think it would be a very good idea,” Eisner told Shooter, joking, “because the Spirit would kick the shit out of Spider-Man.”

Shooter didn’t laugh.

Give it some time, think about it,” he said.

“I don’t have to think about it,” Eisner said. “The Spirit would make a fool out of him.”

Shooter recalled that Eisner was not just skeptical of the mano-a-mano interaction between the characters.

“At the time, I barely knew what The Spirit was—and what I did know was because of Jules Feiffer’s book, The Great Comic Book Heroes,” Shooter said. “Will could not abide by anyone else handling the Spirit in any way. I suggested he could draw it, but he said no. It wasn’t happening. And the state of Marvel Comics in 1978 was pretty ugly. We weren’t good then. I didn’t blame him for being skeptical of our ability to do a good job; he was rightfully worried about the notion of us messing with his character.”

Still, the old Eisner charm took the sting out of rejection for Shooter.

“Will was even nice when he was telling me to go to hell. Made me look forward to the trip!”

(c) 2005, 2015 by Bob Andelman. All Rights Reserved.