Review by Elif Batuman

London Review of Books

April 10, 2008

The term ‘graphic novel’ is dismissed by most of its practitioners as either an empty euphemism or a marketing ploy. As Marjane Satrapi puts it, graphic novels simply enable ‘the bourgeois to read comics without feeling bad’; according to Alan Moore, they allow publishers to ‘stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel’. Moore and Satrapi, in common with many others, want their work to be known as ‘comics’. But ‘graphic novel’ can usefully designate a certain type of comic: a single-author, book-length work, meant for a grown-up reader, with a memoiristic or novelistic narrative, usually devoid of superheroes. By contrast, the older and more capacious term ‘comic book’ recalls the thinner, serialised, multi-authored or ghost-written publications rife with Supermen and She-Hulks. Some comics, of course, straddle (or elude) both categories; but in broad terms ‘comic book’ and ‘graphic novel’ serve to distinguish two trends in the history and form of comics.

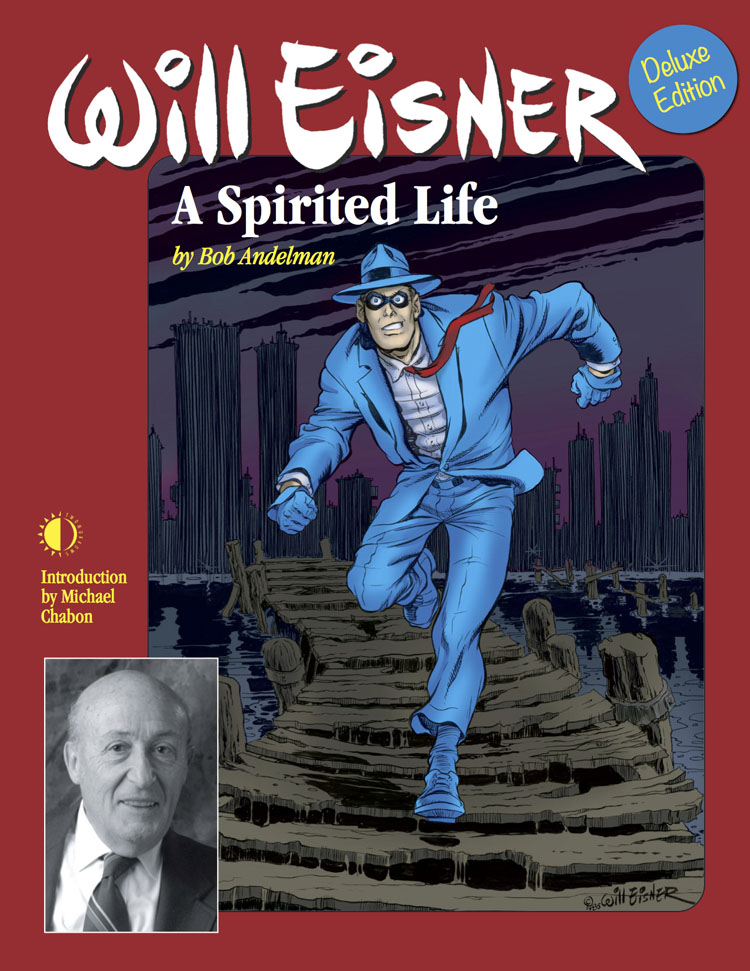

There is no better vantage-point from which to view these two trends than the new collection of Will Eisner’s autobiographical comics, entitled Life, in Pictures. Eisner’s career is a microcosm of the history of American comics, starting with the ‘golden age’ of the 1930s and 1940s. When he was 19, Eisner co-founded one of the first comics studios, Eisner & Iger, whose original titles included Sheena, Queen of the Jungle and Blackhawk, as well as the underappreciated Mr Mystic and Doll Man. Mr Mystic – his real name was Ken – crashed a plane in Tibet, where the ‘Seven Lamas’ tattooed an arcane symbol onto his forehead, endowing him with the ability to transform into animals. Then there is Darrell Dane, a research chemist with the ability to ‘compress his molecular structure’ until he has shrunk to a height of six inches; the Doll Man’s crime-fighting techniques involve hiding in handbags, bivouacking in pie dishes and riding a German shepherd dog. In 1940, Eisner created his most famous masked hero: The Spirit was a syndicated series featuring a former detective called Denny Colt who staged his own death and took up residence in a graveyard, whence he made periodic forays into the world of crime.

The virtuosity of The Spirit is such as to belie the idea of a comic ‘strip’. The panels, as if themselves infused by an exuberant ‘Spirit’, leap from their rectangular boxes, assuming the forms of diverse print media: file cards, gravestones, film strips, children’s books, television sets. Eisner’s panels often float against black Expressionist nights or lightly inked Center City skylines. Some scenes are framed by purely visual devices: the beam of a flashlight, the viewfinder of a telescope, the jagged outlines of a bombed wall, the round windows in the door of a restaurant kitchen. Speech bubbles are made to coincide with pillars of cigarette smoke.