Much is known about Will Eisner’s fabled early days with Jerry Iger and his subsequent departure to create The Spirit, as well as the period of time when he re-emerged with the reprinting of The Spirit by Kitchen Sink Press and Warren Publishing, right through his development of graphic novels from A Contract With God to The Plot.

But little is known about what Eisner was doing between the end of The Spirit in 1952 and his life-changing first meeting with Denis Kitchen in 1971 at Phil Seuling’s annual comic book convention in New York.

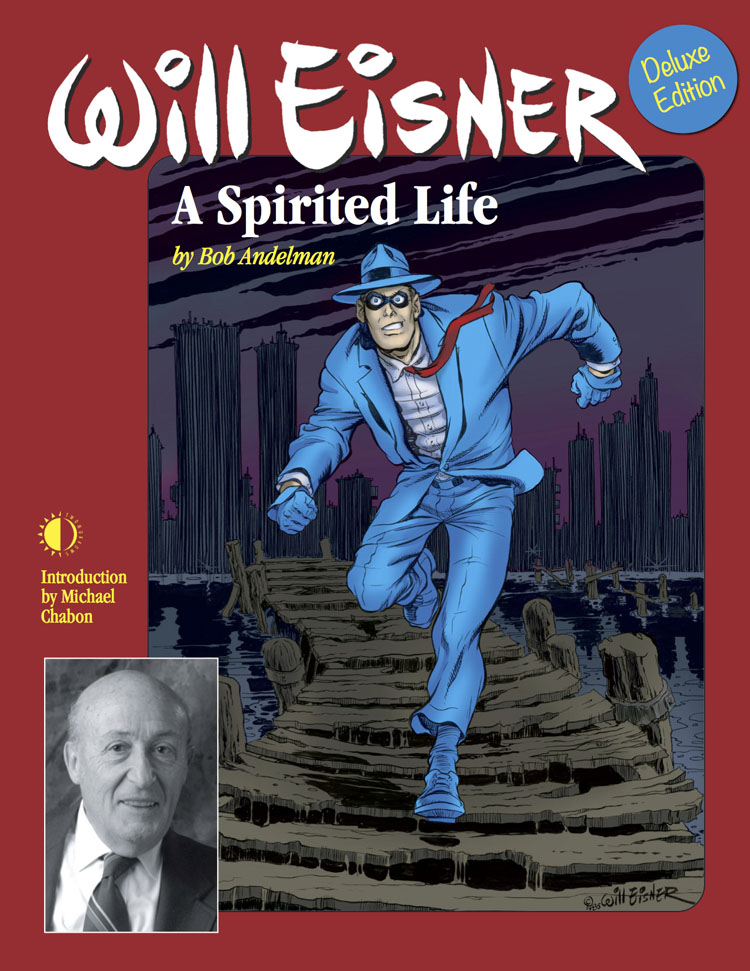

A great deal of information can be found about this period in my biography, Will Eisner: A Spirited Life, but Ted Cabarga was actually there.

Cabarga joined Eisner’s American Visuals as art director in 1959 and stayed until it closed in 1971. The company did a variety of publishing work, most notably its 20-year run on the Army preventive maintenance digest, PS magazine.

Cabarga, his wife and their five children (his son Leslie is a respected illustrator and lifelong comic book fan) dropped out of the rat race when American Visuals closed. They sold their house in New Jersey, embraced the hippie lifestyle, moved to California and lived in a warehouse for a time. Eventually – slowly, he says – he got back into the art business, doing freelance record design for Crystal Clear Records and artists such as Charlie Musslewhite, Taj Mahal, Diahann Carroll, Laurindo Almeida.

For the past 15 years, Cabarga has been a partner in Winning Directions, a business that produces political literature for the Democrats.

Ted Cabarga, today, partner in Winning Directions.

(Photo courtesy of Ted Cabarga.)

BOB ANDELMAN: Can you tell me a little bit about how you first came to be working with Will?

TED CABARGA: It was purely accidental. I came to New York in 1959. I had been in Washington, DC, working, and I wanted to get a job in New York, so I went up there and applied for a job at American Visuals.

ANDELMAN: Did you know anything about the company or Will?

CABARGA: I will tell you, the funny thing about it was that I had seen The Spirit as a young boy of fourteen, in Cuba. My father is Cuban, and I went to visit my grandparents down there, and they had the Sunday supplement of The Spirit in the newspaper in Spanish. That’s how I first saw The Spirit, and I, of course, just loved the drawings because it was far and away better than anything I had seen in comics. So when I got the job at American Visuals, I remembered the Spirit from Cuba, and so right away I had something of a contact with Will Eisner, but not much. He was doing PS magazine, and that’s what I was hired primarily to do, the layouts for PS.

ANDELMAN: Okay. And that would be when?

CABARGA: 1959.

Ted Cabarga in the 1960s at American Visuals.

(Photo courtesy of Ted Cabarga.)

ANDELMAN: Did you know Paul …

CABARGA: Paul doesn’t ring a bell.

ANDELMAN: Paul Fitzgerald?

CABARGA: No, I don’t know him at all. I will tell you who was working there during the time I was there. The primary illustrators were Chuck Kramer and Dan Zolnerowich.

Then they would hire a third, sometimes a fourth, illustrator, but those guys sort of came and went. The two mainstays were Chuck and Dan. The rest were just production staff, but they were the only illustrators. Let me just say that Murphy Anderson came later, as did Mike Ploog, and there was a guy who was there off and on named Gil Eisner, who was no relation to Will.

ANDELMAN: That’s a name I haven’t heard before.

CABARGA: Yeah. Well, he was, I think, the art director for the Village Voice after that for a while, and he had also been an Olympic fencer. So let’s see, who else was significant? Then there was Frank Chiaramonte, this was at the very end. Frank was an illustrator, and I think he has had a good career in comic books, but I am not sure where the heck he is now. He was very good. So it was mainly Murphy Anderson and Mike Ploog and Dan and Chuck during the time I was there. Those were the main illustrators.

|

|

|

ANDELMAN: In my biography of Will, there is a whole chapter about PS, and people just don’t know much about that time. Was it just a job? Was it interesting in any special regard for you? You stayed a long time.

CABARGA: Well, I had a family. I had a pretty good job, and so I held onto it. It was a pretty routine thing, you know, churning out that magazine every month, and it could get very hectic, and I still have nightmares about it, about missing deadlines.

ANDELMAN: Why was that? Was Will a tough guy to work for?

CABARGA: Well, he wasn’t the easiest person to work for. In addition to being the art director of PS magazine, I also had to take care of his other projects, various mail order projects and things like that, and he would do layouts. He would do these crazy layouts for his commercial projects, and they were very difficult to render to make sense out of and to actually do the production on them, so it was a pain in the neck.

ANDELMAN: Can you give me an example? That’s interesting.

CABARGA: It’s hard to remember. He would do a flyer, say, to sell some product, some book or something. We would do books occasionally, then he would do these flyers to promote them, to mail out, I guess. He would do the layout sort of like in a comic book format, and they were just very, very busy. Very busy, and here I was, I wanted to do some nice clean Madison Avenue layouts, but I had to deal with his concepts, which were very busy and confusing and difficult to render. It’s hard to explain beyond that. As for him, there is so much to say about Will Eisner. I don’t know where to begin.

ANDELMAN: Anywhere you like is fine with me.

|

|

|

CABARGA: First of all, he was a great artist, as you know. He was just an amazing drawer. You don’t run into too many people like that in a lifetime. I admired him greatly for his talent, but to work with him was not easy, just personality things, nothing particularly wrong with him. We just didn’t suit each other. We were basically incompatible, so that’s really beside the point, because that gets me and my personality involved in it, and that’s not important. The thing was, I found him difficult to work with. He would change things, and what he did seemed arbitrary. But again, that’s not important, but it’s just my personality clashing with his. I think people in general who worked with him… do you know Klaus Nordling?

ANDELMAN: I have run across his name. I did not speak with him.

CABARGA: He used to work with us and do illustrated books, and he also had a little difficulty with Will, so I guess Will wasn’t the easiest person to work with. When it came to PS magazine, Will’s obligation to the contractor (the Army) was to do the continuity, the comic centerspread of the magazine, and he would pencil it out, and then he would try to get Chuck to ink it, because Will was always trying to get out of doing PS magazine.

ANDELMAN: Really?

Will Eisner in the 1960s, while running American Visuals.

(Photo courtesy of Ted Cabarga.)

CABARGA: Yeah, it really became a drag for him, and when he finally lost the contract, I am sure he was very relieved and happy to get out of it. It had gone on for fifteen years or more, twenty years maybe, and it got harder and harder for him to get himself into the mood to do it, so it was like pulling teeth. We would have to try to get him to come out of his office and come back to the bullpen and do the inking or the penciling, as the case may be. So yeah, I think that he really was happy to see the magazine go. It became a drag.

ANDELMAN: Now, you said that you guys didn’t see eye to eye, but you were one of the longest-termed employees that he had. Something besides a family must have kept you coming back, or was that it?

CABARGA: I am not really a comic book person, you have to understand that, but my son Leslie has a comic book background and orientation. He loves the comics, and he wanted to be a cartoonist, and I wasn’t coming from there at all. I don’t really care for comics, and although I just loved what Will did and I realized how great he was, I still was not interested in that whole field. So I held onto the job just because it was a steady job and it was a good job but not out of any particular affinity to what Will was doing or my love of that stuff.

But again, what I am saying is, I don’t want to concentrate on my personality, because that is not important. I want to try to talk about Will as much as possible. I don’t know.

|

|

|

What else about Will? His working habits were not too good because, as I say, I don’t think he wanted to do it, and yet he did it so well when he did do it. I used to read those continuities that he would do and just laugh my head off because they were so good.

Chuck Kramer was always in a rivalry with Will. Chuck thought he was as good as Will, and he couldn’t see the difference between the two of them, and he would constantly be carping and complaining about Will, because it was hard to get Will to do the work on time. But of course, Chuck, in reality, was a very good illustrator. He didn’t have the personality or the mind of a Will Eisner, so he really was not in his league in any sense except just the raw drawing, which he was very good at.

ANDELMAN: You said it kind of fell to you to get involved with some of Will’s other lines. He was selling stuff to students…

CABARGA: Unfortunately, I am kind of vague on those products, too. I didn’t think a whole lot about them. I didn’t like them very much.

ANDELMAN: But you know what I am talking about.

CABARGA: I am not exactly certain. He was always trying to take the concept of teaching with cartoons out of the military and applying it commercially as well, so he was coming up with these products, and frankly, I can’t remember anything much now.

ANDELMAN: One of the things that I have heard from a number of people, including Jules Feiffer and Mike Ploog, was that Will was cheap.

CABARGA: Yes, he was. He was fair, but he was very cheap, and in fact, I believe that he really destroyed his own business that way because he wouldn’t invest the money to do things properly, and he was always trying to recycle things. All the time I was there, he was always trying to re-sell the old Spirit stuff that he had, hundreds of issues in the archives. He was constantly trying to repackage it and re-sell it, and he just didn’t promote things properly. He didn’t put the investment into it that would have been necessary in order to successfully promote his product. He was cheap. Like I say, he was fair. He was always good to me, but he was tight.

ANDELMAN: I guess Ploog toldhttp://www.blogger.com/img/gl.link.gif me a story that someone on the staff at one point had collected all the and done like a belt.

Artist Chuck Kramer at American Visuals during the 1960s.

(Photo courtesy of Ted Cabarga.)

CABARGA: That was Chuck Kramer. He would use the pencils pretty far down, and then he would keep them and make like a cartridge belt out of them. Now that may have originated from Will wanting them to use the pencils up instead of throwing them away when they were still long, the blue pencils. It might have originated from that, so he was trying to satirize the situation.

ANDELMAN: Do you remember when Will’s daughter died? Anything you can tell me about that period of time?

CABARGA: Yes, I do. I can tell you that Will really changed after that. He mellowed out, and he became a much nicer person. Yeah. It was amazing.

ANDELMAN: Really. Do you remember how you heard about Alice?

CABARGA: He was very secretive about it. I tried to look back in retrospect and see if there had been any indication that anything was wrong before it happened, and I couldn’t really put my finger on it. I think he was kind of withdrawn and grumpy a little bit but nothing really very specific. But then suddenly we found out that she had died, and we all went to her funeral. So I say, after that he mellowed out and became a nicer person.

ANDELMAN: Had he ever brought the kids to the office? Had you even met them at the time?

CABARGA: I think I had seen them, but I don’t recall anything specific along those lines.

ANDELMAN: The years that you were there, they were probably just a couple of years old when you started with him and they grew into teenagers.

CABARGA: Yeah. That’s why I am pretty sure that I must have seen them in the office, but I have no particular recollection of them at all.

ANDELMAN: Of course, it is a very different era now in the office. People tell you everything about their lives. Thirty-five years ago, they probably ….

CABARGA: Will certainly didn’t confide in me about it, because Will and I were not close in that sense. I had no idea of his family life from him. He didn’t talk about it.

ANDELMAN: Did you guys put in a pretty standard day in the office? Was there a lot of overtime?

CABARGA: We would get into overtime on PS magazine not infrequently, and then it could be a really big grind. The editors were very demanding. Much of the time, they felt insulted because Will would not give them the attention that they wanted. It was a routine matter that we would fly to Ft. Knox once a month to review the dummy, which was the basic first edition of the magazine, first draft of the magazine. We would send it to them, and they would review it, and then we would go down there and sit there for a couple of hours with them while they discussed all the changes and things that they wanted, and that was their big moment when Will Eisner would go down there and talk to them. Will was a very charming person, very bright, charming, witty, and so he was fun to be with and fun to talk to, so that was the highlight of their month when he would come down there. And as time went by, he would weasel out of it, because he got more and more bored with the whole project. He would weasel out of it for one reason or another, so they began to feel insulted, and that is ultimately, really, why he lost the contract, because they were just so miffed with his not paying attention to them any more.

|

|

|

ANDELMAN: What was he interested in at that point?

CABARGA: Well, it would be hard for me to say, because he was running this business, and I always felt that he shouldn’t have been running a business, because I didn’t think he was doing it terribly well. He was always trying to come up with these schemes, these promotions of one thing or another and never being very successful at it. I felt that he had a compulsion to be a successful businessman, whereas what he should have been, what he was best at was what he did later when he was on his own and just doing the books, the illustrated novels. I don’t know if he really found himself then when he quit trying to be a businessman and just did the novels. I don’t know if that was making him happy, because, of course, that was long after I was out of touch with him, but that is what he should have been doing, and I hope that that was what was making him happy. I hope he finally realized that he was wasting his time.

ANDELMAN: To be honest, I think that he was very proud of his time in business, and I think that from talking to him, and I spent a lot of time talking to him, he took great pride that he was a businessman.

CABARGA: Really?

ANDELMAN: Yeah.

CABARGA: Well, my speculation about it was that, I thought that it was his father who had probably disparaged his drawing, his artwork, and saying like parents are typically supposed to do, they say, “Oh, get a job! Don’t fool around, don’t try to be an artist, you can’t make any money that way, do something legitimate, be a dentist or something.” And I had the impression that it was probably his father who had taken such an attitude, and therefore Will, to try to solve that problem or please his father, tried to be a businessman rather than just an artist, and I later found out that it was his mother…

ANDELMAN: Okay, I was going to say, yeah, it was definitely his mother.

CABARGA: In one of his novels he talked about that, so it turned out that it was actually his mother that was trying to discourage him. So I thought that that was sort of eating at him and that that was why he had this image of himself, that he wanted to be a businessman rather than just an artist, which is ironic, since he was a great artist and a lousy businessman.

ANDELMAN: What was Mike Ploog like to work with?

CABARGA: Ploog was terrific. I just have to tell you that Murphy Anderson, poor Murphy Anderson, he was the most wonderful guy in the world, but he was slow, and he would work nights, and he would work two weeks in a row overtime late into the night trying to get the book inked. Ploog, when we were finally across the street and away from the office and we were running our own sort of little mini-business there getting out PS magazine, Ploog would come in and ink the whole damn book in one day, and he was just stupendous. When he first got there, his art was a little tentative, because I guess he was cowed by the great Will Eisner, but very soon, within a few months, he was in stride, and he was just very fast and very good.

ANDELMAN: What was he like to be around?

CABARGA: He was a great guy. He was a mesomorph; he was built like a fire plug. He had these big arms. He was a little guy but very stocky and sturdy, and he had come from the West Coast. He was working at Hanna Barbera. I don’t know why. I guess he wanted a change or something, so he was hired from the West Coast, but apparently he wasn’t happy, because he finally went back there. During the time that I knew him, he was very congenial, very nice in every way. I had no problem with him. As I say, he was really very good.

ANDELMAN: And Dan Zolnerowich?

CABARGA: Dan was a good guy, too. I also had an assistant art director working with me, Gary Kleinman. Have you heard his name?

Gary Kleinman and Gil Eisner (no relation to Will Eisner) at American Visuals in the 1960s.

(Photo courtesy of Ted Cabarga.)

ANDELMAN: That name is familiar a little bit.

CABARGA: Yeah. Gary Kleinman was assistant art director for a few years. I don’t remember how many but maybe as many as five or something. At one point, Gary and I got really pissed at Kramer and Zolnerowich, because we felt that they were featherbedding and in so doing were hurting the whole operation. They would delay the production of the artwork, and that would force the production people to give us less time to finish the book. We really felt like we were being cheated by them. So at one point, Gary and I confronted them and just really laid it on the line, and they thought that Will Eisner had put us up to it. That was absolutely not true. Will had nothing to do with it, and I could never convince them that Will was not behind it, that it was us who were pissed off at them, not Will. But after that point, there was a rift, and we were never the same again. Dan and Chuck had their quiet little clique, and we were no longer friends, but before that, we had been good friends. Dan was a pretty solid guy. He was not really a cartoonist. He sort of like did the technical stuff.

|

|

|

ANDELMAN: The years that Will was involved with PS, he really was kind of out of the whole comic book thing, but did you ever have comic book fans pop up at the office looking for the “great” Will Eisner?

CABARGA: Probably. I don’t exactly remember such things. I am sure it must have happened, but I don’t have any specific recollection of that.

ANDELMAN: I want to ask you again about Will and money. One of the things that he told me that drove him crazy was that when the folks down at Ft. Knox would want changes. I don’t know if he said that; maybe Ploog said that, that they would want changes, and it drove him crazy because it meant overtime, and it meant more cost, and it cut into the budget.

CABARGA: Absolutely. When I was talking about them being insulted by Will’s unwillingness to come and talk to them and see them that part of the way they punished us was to get very, very chickenshit with us and watch every comma and every line space and every tiny little thing that they could possibly find wrong with the book. They would call us on it and make us re-do it, and that was part of that whole thing of costing money.

ANDELMAN: Do you remember anything about his habits in terms of, would he bring his lunch to work?

CABARGA: Will? I don’t think so.

ANDELMAN: I never got the sense of him being a going out to lunch guy, even if he was going out by himself.

CABARGA: He did go out by himself. The funny thing is that those little details have just completely escaped me. You know about his brother Pete?

ANDELMAN: Yeah. Now, did Pete work there at the time?

CABARGA: Pete was his whipping boy. Pete was the production manager. He ran the nuts and bolts of the business, and Will would continually beat him into the ground and scream at him and pick on him. Poor Pete was just very harassed and running around and doing everything. He sort of had an adoring attitude toward Will. He was his slave. He never seemed to complain. He put up with it. I don’t know why. Will really, really mistreated him.

ANDELMAN: Wow. Can you think of any examples, anything that stands out?

CABARGA: The only thing I can think of is that he would scream at him for making mistakes and doing something wrong, and Pete would try so hard. No, unfortunately, I can’t remember any specific thing.

ANDELMAN: I did get to know Pete, and you probably wouldn’t know this, but Pete continued to work for him. Right up until the day Pete died, he was working for Will, running his office.

CABARGA: When did Pete die?

ANDELMAN: Will died in January of 2005, and I want to say that Pete died in December of 2003.

CABARGA: Okay. So you are saying that they had an office up to that time?

ANDELMAN: Yeah. Oh yeah. They lived like literally around the block from each other in Florida, and Pete ran the office and was the gatekeeper there.

CABARGA: Yeah. Well, you see, that’s what he was doing all his life. I didn’t know that.

ANDELMAN: What I found was that they had more of a playful attitude with each other that could be… It was clear who the boss was.

CABARGA: Yeah, I bet it mellowed out later on. That’s probably what happened, because it was really pretty one-sided when I was there.

ANDELMAN: Did Will use Pete as kind of the go-between with the staff? I mean, if you had a problem, would you go to Pete, or would you go to Will?

CABARGA: If it was a production thing, sure, we could go to Pete, but if it had to do with art or anything, no, we would go to Will. But Will generally tried to stay out of the art department. It was almost like he was embarrassed to be an artist and be associated with us in a funny sort of way.

ANDELMAN: So I guess there is no point in asking if there is anything that you picked up from him over the years if he was kind of hands-off about that stuff.

CABARGA: Remember, I wasn’t an illustrator. I didn’t do any art work in that sense. I did layout. Once I did some illustrations for one of the books he was doing, and he looked at an illustration of a hockey player that I had done, and he harrumphed and said, “Out of drawing,” so that really miffed me. I didn’t know what he meant by “out of drawing,” because when I looked at it, I didn’t see any way that you could possibly say it was out of drawing, but apparently he didn’t like it. But I had very little artistic association with him in that sense.

|

|

|

ANDELMAN: Tell me about the last time you saw Will. I guess that was when the office was closed down.

CABARGA: I don’t remember any particular time. It just petered out. What happened was, it went by stages when I think Chuck and Dan continued doing the illustrations. For some reason, Will took the production department and shipped us across the street into a separate office, and he put us on a budget, which we had never been before, and we could spend the budget to do the magazine, and we could keep whatever money was left over. So that went on for maybe a year.

ANDELMAN: Was that Ploog and Kramer and you?

CABARGA: No. By then, Chuck and Dan were gone, and Ploog was doing the illustrations, Ploog and Frank Chiaramonte. And those two were doing the illustrations, and we were in this other office across the street, and that went on for about a year. I saw Will less and less, then not at all. As I said, we were not close. There was not something I was dying to see or relate to Will Eisner.

ANDELMAN: Anything else you recall about Will? So many years that you were there with him, anything else stand out from that time?

CABARGA: I guess I am trying to forget most of it.