There aren’t many successful brother acts in comics. One of the first was Stan Lee and Larry Lieber; one of the best known today would be Joe Kubert’s sons, Andy and Adam .

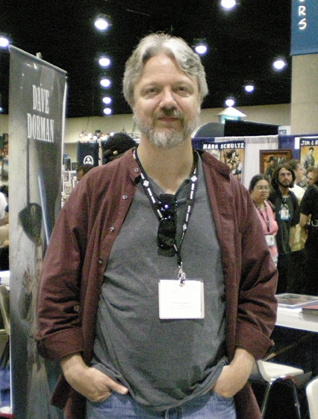

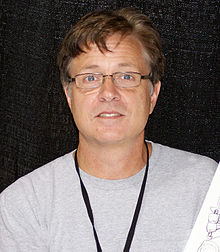

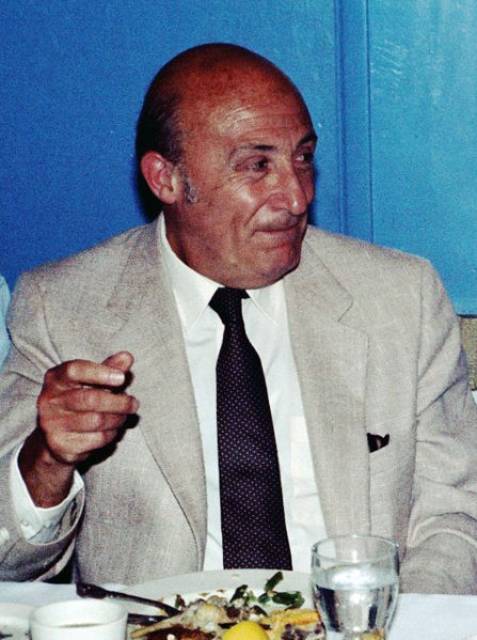

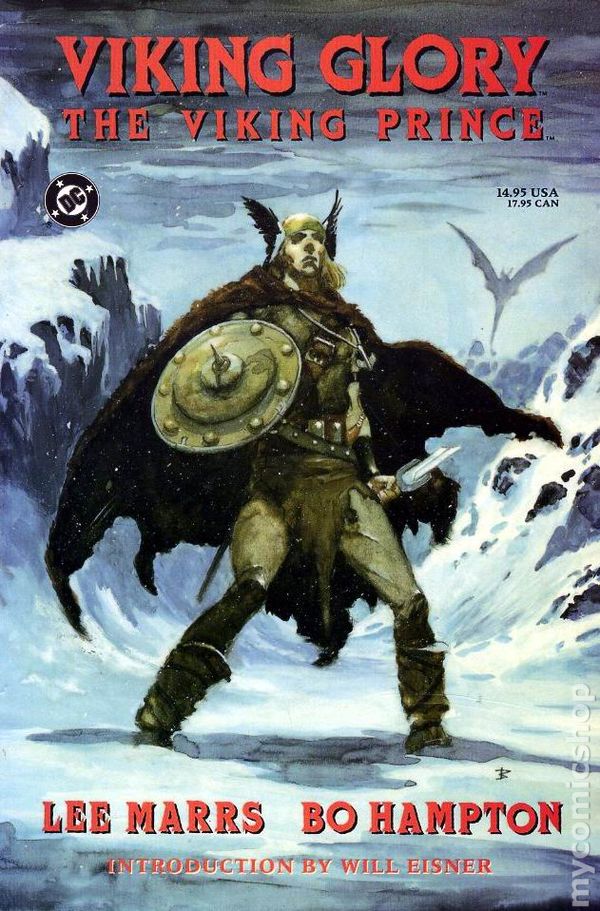

The Hampton brothers, Scott and Bo, have made been making two distinct impressions on the business as artists for more than 25 years. Bo, the older of the two native North Carolinians, studied under Will Eisner at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. He later spent a year as Eisner’s production assistant at his home studio in White Plains, NY. That summer, he brought his younger brother, Scott, along to help and learn one day a week. That experience had an enduring impact on both of their careers and continues to influence them today.

It also left them with some wonderful, never before published stories about Eisner.

BOB ANDELMAN: What was the first that you ever heard of Will Eisner?

SCOTT HAMPTON: I can recall that exactly. I was at a friend’s house, and he showed me the two Harvey reprints of The Spirit, and correct me if I am wrong, those were by Harvey?

BO HAMPTON: I saw the Harvey reprints and loved them. I was about 10 years old so it was around ’64.

ANDELMAN: Yeah, they did two of them in the ‘60s.

SCOTT: I’d never seen his work before that. I’m not sure when Warren started to reprint the Spirit material, and so it’s conceivable that I had seen a little bit of it before I saw these Harveys, but I hadn’t really taken it in. I wasn’t really thinking about what it was. When I saw the reprints, I was just amazed and read them immediately and was just floored and became an immediate fan.

ANDELMAN: How old were you when you saw the Harvey reprints?

SCOTT: I would say this was when I was 15.

ANDELMAN: How old are you now?

SCOTT: I’m 47. I was born in 1959, so it was in about 1974 or 1975.

BO: I’m as old as the wind…52.

ANDELMAN: So it must have been the Warren reprints that you saw.

SCOTT: No. I had seen those. I may have seen some of them, but what I was seeing that knocked me out were the Harvey reprints from the ‘60s…

ANDELMAN: Oh, because they were in color. Oh, okay.

SCOTT: Right. Well, not just that. They were comic books. They were comic book size, and yes, the color was fabulous, I thought. Again, it’s been a long time since I saw them, but I just felt like this is a man who knows how to draw for that form of reproduction, using the limitations of a four-color process. There are certain artists who know the limitations and then try to make their art work within that limitation. It’s one of the great challenges of doing stuff for reproduction. So I think Will was an absolute master of it. Alex Toth was a master of it. I think that the color work by Marie Severin on the ECs is a fabulous collaboration between her and the entire clan of artists that Gaines had. They knew what they were dealing with, and they worked within those parameters.

ANDELMAN: Right.

SCOTT: So yeah, but that compilation, those two reprints just blew me away.

ANDELMAN: So you were fifteen years old. What are you thinking at that time you are going to do with your life?

SCOTT: Oh, I’ve known that for as long as I can remember. I was going to be a comic artist. We should backtrack for a second to say that my brother, Bo, he is a bit older than me. I’m not going to say he’s lots older, because he would be upset, and he’s not, but he is old enough to have been a complete influence on me, so whatever he was into, I was into, and he was the one who brought comic books into our world, and he started drawing, and I started drawing. I don’t know what I would have ended up being had I not had Bo for my older brother. So I knew I was going to pursue comics. It’s funny, though, because I’ve been influenced by people who were influenced by Eisner. I just hadn’t known it. So he ended up being the source.

ANDELMAN: Who are you referring to?

SCOTT: Bernie Wrightson. Bo and I had also taken in the work of people like Wally Wood, but I think the person that I was most trying to become at that point was Bernie, and Bernie, of course, had learned a terrific amount from Will, especially regarding inking. A quick segway to Bernie. Now we go into the future when my brother is apprenticing for Eisner, and I am there as just the kid who is hanging out and helping out in whatever way I can just for fun and learning on the side, but I wasn’t an official person. My brother was. But I was there, and Bernie’s name came up, and Will was talking about his brush line, and he told the story of how he and Lou Fine had had their competition with a Japanese brush to see who could keep continuing to do the line without thickening it the most times, and Fine won. But he said, “I still have one of the best lines,” and Will was not somebody who just walked around pumping out his chest. But he said, “I’ll put my line up against most anybody through the years. Maybe Bernie Wrightson is more facile than I am, but who knows.” So he naturally mentioned Bernie, but of course, Bernie will admit if you have ever talked with him that Eisner was an influence.

ANDELMAN: I actually hadn’t heard his name come up before. No, really. The world is so big when it comes to Will that….

SCOTT: Again, you can look at the trapped shadow technique, and you can say, who started that? Was it Lou Fine? Was it Jack Cole? Was it Will Eisner? But I don’t think Bernie would have gone there had he not been studying that school. Again, I’ve talked with Bernie, and he does admit that Eisner… he doesn’t admit it grudgingly, he will tell you that Eisner was an influence on his work, and it was not just the brush lines. It’s the chiarascuro quality and the cinematic aspects. When Bernie throws a contorted shadow on the wall, that’s not just German expressionist, it’s Will Eisner.

BO: Eisner’s dad worked as a muralist and a set designer. Will’s early life, as he related it to me, was spent with a regular exposure to theatre lighting. You can’t put a finer point on it than that, really. He saw that stark, double lighting on the stage and it carried over into his work. Probably true of Wood as well.

ANDELMAN: At some point, as you mentioned, Bo started working for Eisner. Now am I jumping ahead in the story here?

BO: In 1973 I found out Eisner was teaching at the School of Visual Arts in New York and determined, based solely on that fact, to attend for the remaining two years of my college career. When I got in his class in 1975 I was so thrilled. Finally, I had true art training. All the other “art” courses I had prior to that had stressed “non-representational” art and it was anathema to me. I loved American illustrators like N.C. Wyeth, Pyle, etc., and they were totally out of vogue. In Will’s class in Sequential Art 1, I could finally do what I had always dreamed of doing, which was comic art. In that one class there were at least three students who became pros – Alex Saviuk, Walter Brogan and me. Will would trace over one of my panels in order to straighten out the perspective and he always drew what looked like a shoebox but without a top in which the characters would reside and I realize now, once again, it looked an awful lot like a theater set. After my two years at SVA, Will asked me to become his assistant and I was glad to continue picking his brain in whatever capacity he would have me.

In ’77 I started working at the “Poorhouse Press Studio” in back of his White Plains property. I took the commuter rail to the studio five days a week at first and eventually I would go in for only three or four because I would take work home. But when I arrived in the morning he always picked me up in that old red Dodge Dart that smelled like cherry-blend pipe tobacco. I was 23 at the time so I was pretty bleary at 8:30 in the morning but Will was a “morning person.” I never saw him drink coffee – he probably imbibed several cups after waking up at 6:00 or whenever. But I always kicked it into high gear when he drove up because I knew he would be cordial and come up with interesting reasoned responses to any question I might have had – no matter how inane – and there were many.

SCOTT: It was over the course of one summer when I came to visit Bo in New York. He was living in an apartment on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, and Bo would go in and work at Eisner’s studio and I went in one day a week with him. We would just go to Penn Station, and we would catch a train out to White Plains, and we would be met at the station by Will. We would work there all day, then he would take us back to the train station, and we would head back.

At the time, Bo was helping Will prepare A Contract with God, and Will had determined that he wanted to print it on slightly different paper, maybe an off-white paper, and print it in brown ink and all this, and we are going, “Wow, that sounds great.” But he also wanted to include a bunch of tones, which I guess was the sepia. It was a technique he was using in his Spirit reprints for Warren and other places. He was taking black and white artwork that had been intended for color and just using it with some grays, and I think that he just was in the habit of doing that.

But the honest truth is, I think, honestly, that Will may have had it in his mind that he didn’t know what he wanted to do, so he would go ahead and get Bo, and at those times I was there, me, to do this work just in case. I don’t know. He may not have been decided, but at some point in there, we did turn to him and say, “Look, we don’t think this is helping. The line work is great already, so we think you should print it without these tones.” And I don’t know that he hadn’t been told that by other people, too, but as you know, he didn’t end up using the tones.

To get in my best anecdote about Will, I was working in the studio at one of the drawing tables. It was early in the morning, Will was smoking a pipe and talking away on the phone with some stockbroker, which he did almost every time I was there, and Bo told me he did that almost every morning. I think he may have been able to work while on the phone; but he certainly did multi-task well. Will had given me roughs of “The Street Singer,” which is to say he had spotted where the tones needed to roughly be, and he had done this on Xeroxes, and then I was to take the piece of paper on which he had drawn it, take the original, affix a piece of acetate over it, put the registration marks down, and then apply a red dye to the areas where the gray will be, and then that’s what he would send to the printer. Well, I guess I had a mental fugue or something, but I found myself applying the red dye directly to the original one time, and I was noting as I did it, “Wow, it’s going on… it’s got a lot more grip to it. The acetate is usually slippery; this is unusual.” And I had gotten a little way into it when I realized I was working on the original. I was very anxious about that, I can assure you.

ANDELMAN: Who did you go to first, your brother or Will?

SCOTT: I don’t remember. I think I went to Bo first because I didn’t know quite how to handle it, and I also might have thought maybe he would just fall on the sword and say he had done it or something. But in any case, I finally went over… Bo did not fall on the sword, and I went over to Will, and I said, “Mr. Eisner, I am afraid I have done something bad here,” and so he looked at it, and he looked up at me, and he took his pipe out of his mouth, and he just kind of sighed, and he went, “You Hampton boys will do anything to get an original.” So he then took an Exacto blade out, he cut out the panels, and I have it to this day, it’s the one where the woman has thrown the note down to the singer in the alley, and he is looking up with the note in his hand, and it’s that panel that he pulled out. He handed it to me, and then he proceeded to put another piece of paper down to redraw it from scratch without even looking at the one he had already done. If it were me, I would have found some way to send the assistant away and found a way to white-out all that stuff to use that original. But instead, he didn’t even look at it, and he drew it again while I was watching. I was just amazed. He looked at me, and he said, “You know, I think I improved it.”

ANDELMAN: Wow. That is a great story.

BO: In the studio, prior to Scott’s illustrious arrival, Will and I would work on Spirit stories. I would do grey tone overlays and touch-ups and Will would actually go in and add crow-quill pen lines or even brush work in panels that needed to be clearer or cleaner. And he was doing that on the “original” Spirit pages. I drove with him to the “vault” occasionally to pick up a few of the 7-page stories and I’m not kidding it was in a vault in some kind of securities/exchange building in Manhattan. The pages were huge, like 19” x 13” and had crumpled corners and rubber-cement stairs all over from where the lettering or an art paste-up had lifted off or been removed. So they were in lousy shape and ugly in that sense, but the art itself was some of the best ever done in the medium. That was when Will first told me I drew figures like I had a “pole up my ass.” Which was a colorful way of saying, “Let the people relax. Let gravity affect them.” He showed some beautiful examples of that in the Spirit pages and when I asked him about the backgrounds, he said the guy he liked a lot was Jerry Grandenetti. And of course that was one artist nobody could accuse of having a pole up his ass. Will’s point was almost like it was an ethnic thing, like this Italian guy Grandenetti is a relaxed guy and it shows in his art. I still get a sting when I remember Will telling me that but it was what I needed to hear when I needed to hear it. He knew I could handle it, I guess, by then. But the great thing about Will’s instruction was that with every barb came a bolstering compliment about another aspect of my work which was true as well. He kept that balance.

SCOTT: What a gracious guy, what a first-class guy. And the other thing I remember about going in there was that I did show him my portfolio, and he said that there were some nice things here and there, but he then pulled out a drawing I had done in ink, a drawing of Ebenezer Scrooge the morning after waking up, and he is elated, and he stands up in his bed with the four posts all over, and he is like going, “Hurrah, I am alive.” So he said, “See, your man, Scrooge, is very stiff and doesn’t have any life. Now look at my man,” and he pulled out a drawing from one of the things he had just done, a shot of one of the characters raising his arms with all this ribbon and all, and he said, “See, the difference is that my man actually seems to have life, and that’s because there is an element of the cartoon in what I am doing as well as realistic technique.” And of course, I was coming from a very different perspective at the time, and so I didn’t tell him that I thought that he was wrong. I felt that he was wrong in saying that. It took me a long time to realize how right he was. It was only much later. That’s the thing, and that really did make such an impression on me not then but later. I began to realize, students can’t always hear the truth. They are not sophisticated enough to know it when they see it. They have blinders on. In order to aim them in the right direction, you can’t expect them to just get it, so ever since then, if a student looks at me and goes, “Oh, I don’t think that at all, I like the way I am doing it,” I just check myself, and I just go, one day he will figure it out.

ANDELMAN: How long a period of time are we talking about that you were going up there?

SCOTT: It was mostly over the course of this one summer, and it was the summer of my junior year in high school.

BO: I graduated in 77and then worked for Will for one year.

ANDELMAN: Did you meet anyone else while you were up there? I am guessing this is before Cat Yronwode got involved.

SCOTT: No, no. Cat had been involved before that, but she was not there at that time, no. We heard stories about her. I think that Will may have had some stuff that she was corresponding with him about, so she came up, but I didn’t meet her.

ANDELMAN: From what I am recalling from what she had said, she met him for the first time at SVA, and he had showed her the first time they met pages from Contract. I am trying to remember if it was published yet or not.

SCOTT: Wow. Well, now, it’s conceivable that I am conflating the two instances, but I am pretty sure that when I was there, Will had told Bo and then Bo told me about this woman named Cat Yronwode who had come in to see him, and she had Althea, who is now my niece-in-law, in a papoose on her back, so I am trying to think how old Althea is.

ANDELMAN: As someone who wanted to go into comics and kind of following his brother, I imagine there are a lot of things that probably made an impression on you guys that summer.

SCOTT: Very much so, especially the stuff about Will, of course. First of all, meeting Will and getting to know him and see his work ethic and his work habits. We are talking about a guy who had brushes from the ‘40s, still had them.

ANDELMAN: That’s because he was cheap!

SCOTT: Well, there’s that, but he was also careful, and he took care of stuff. That studio was a great working space. It was a beautiful area that he was in, and it seemed like the idyllic, perfect setting for a comics artist. I mean, somehow I always see comic strips and comic book artists living somewhere in upstate New York or Connecticut or somewhere up in the northeast and in these large houses, nice suburbs, and essentially that’s what that was. It was every kind of cliché in my mind of a way to be if you are going to be a cartoonist.

Will was my introduction to the way that you behave toward younger people who are up and coming guys or just guys who want to do what you do. I never spent so much time around an established pro. I had met one or two at conventions, and it was just for a moment, but I got to spend some time with him, and of course, with Will being so influential and so talented, it was that much more…. I don’t know that I realized it then how much of an honor it was for me to be there, but I have come to understand it since. I carry back with me a lot of memories and images from that period.

It’s funny, because he was very conscious of what was going on overseas as well. He had a lot of material that was sent to him by the foreign publishers, and this was, again, my introduction to that. I hadn’t seen or taken note of a lot of the foreign graphic novels. I knew of Moebius through Heavy Metal, but Paul Gillon I had never heard of, and I had never seen the work of some of the other guys. It’s funny, they seemed to be in either the Milton Caniff school or the Alex Raymond school. Gillon was the Alex Raymond school to me. So even though they didn’t seem to be specifically influenced by Eisner, he was very taken with their work and interested in what was going on there.

ANDELMAN: Can you kind of set the scene for people in terms of that work space that you were in? Where was Will? Where were you? Where was Bo?

SCOTT: Well, first of all, you need to know that this was a largish studio in back of the house.

ANDELMAN: It was in a separate building, wasn’t it?

SCOTT: Separate building, right, separated by, I think, a patio, and once you entered, if you looked to the left, you would see Will’s work station, and this wasn’t immediately apparent, there was a Xerox copier, and bookcases.

He looked to me like, at least I remember him, as being surrounded almost by his tools and the desks and all the different spaces that he could use for his work, so he seemed to me like he was a captain of a rocket ship, and he had all these buttons and mechanisms all around for getting where he needed to be. Then I remember that you would have to go further back, you would have to turn 90 degrees from looking at Will and start to walk backwards into the space to get to where the other drawing tables were. Again, it seemed to me that it was very orderly and very well laid out, but again, memory is a funny thing. I just see it as being bigger than probably it was and having more layers of desks and objects and things that were between… I felt like I was miles away from Will when I was working, and I couldn’t have been. But that’s the way it felt. I think Bo’s area was off to the right somewhere from me if you were facing from where Will was.

ANDELMAN: Were you paid for this time?

BO: I was paid. Scott was paid too – as far as Will knew!

SCOTT: Well, Bo was paid, and I was not expecting to be paid, I don’t think, but at the end, Will gave me some money for it, which I was surprised by, and I said, “Wow, thank you,” because to me, it had all been about just being there. But I think he just sort of, as a nice gesture, gave me some money.

ANDELMAN: That was a different era, wasn’t it, where you would do all that kind of work and not expect to be paid? I don’t think you would find a lot of that now.

SCOTT: But in a sense, it’s not that different from today. These days, you can be a working professional and be doing all that work and not expect to be paid, because very many people work for outfits that don’t pay them anything, they just say they will share the royalties at the end.

ANDELMAN: Oh, I see. Yeah.

SCOTT: So there are many publishers these days who don’t pay much of anything, and then it’s just a lick and a promise. So yeah, whereas the apprentice system has always been run essentially as, “Here, Xerox that, boy.” That kind of thing. So I didn’t expect to be paid, and I was happy to do whatever work I could do that was more related to art. And it’s funny. It’s like now, every once in a while, you will have an intern who wants to work with you, and you go, damn, it’s a lot of work to actually have someone about who is looking to you to try to keep them busy.

ANDELMAN: More responsibility than you think of when you are on the receiving end.

SCOTT: That’s right. I felt like it would just be a breeze for him, we were nothing but helping him, but the truth is that we probably were a bit of headache for him at times, and he was looking for ways to keep us being productive.

ANDELMAN: On the train in and on the train back, do you remember any memorable conversations with your brother about what you were going to do or what you had just done that particular day?

SCOTT: Well, there is one. As you know, Eisner is one of the great, great artists when it comes to intuitive perspective for buildings, for cityscapes, that kind of thing. Well, I had done the overlay for a chapter image or some sort of large image of a city, and I had laid in extra shadows, shadows that Will hadn’t put in but which I said, well, if this is the light source, all these buildings will have shadows here, here, and here, and I started filling them all in, and when I got done, I had this abstract Steranko-looking black and white sort of high contrast cityscape done in red on this piece of acetate. If you pulled it away from the art, it just looked like a photograph of a city, and Bo said, “This is a real testament to how well you plotted out the perspective.” And Will said, “I didn’t plot anything out, I just kind of drew it,” So we talked about that on the way back, and our conversation continued well into the evening. We decided we wanted to figure out the plotting for how to create a shadow in perspective, and we didn’t know how to do it except by kind of intuition. So we started working on it, and we worked on it for a long, long time, and by the end of the evening, Bo and I had both kind of together figured out a way that we thought worked, though we had never been taught any way to make this work. Now again, I am not talking about three-point perspective or anything like that. I am saying, if the sun is up in the sky at this point and you have a block sitting on a plane, how do you know how far down the shadow goes on the ground? And so we figured out what we thought worked.

Bo went to Will the next day, and he reported back to me after he got back. Will looked at what we had done, and he said, “That’s it, that’s the way you do it formally. That’s exactly the method for really plotting out how this would work.” Because it made sense to us, that was all we were using was just how we saw it or how we thought it should be, but then there was Will to confirm that it was actually the way that it’s done, and we were both very proud of ourselves, but in the end, he’s right. Will said, “You take in the information, and you learn how to do it right, and then you internalize that, and if you are worth your salt, you then start doing it just intuitively.” I don’t think I have ever plotted out perspective since then much. But I wanted to know, basically, how things worked, and it was all based on this one cityscape of Eisner’s. And that was the kind of intellectual exercise that would come up on occasion. It wasn’t just probing him for old stories about the Eisner/Iger studio or what it was like to work with this, that, or the other person, it was also technical, and he could roll with anything you wanted to talk about.

ANDELMAN: It must have been very cool.

SCOTT: Oh yeah, it was.

BO: Oddly, I remember that about the “shadow-box” and how to draw light in perspective as something Scotty and I pulled our hair out over. Scott figured out most of how it worked. He was great with lighting…still is.

ANDELMAN: Did you have friends who knew and understood what you were doing at the time, or was it just kind of lost on them?

SCOTT: Well, to a certain extent, yeah. Bo met a number of people who took courses with Eisner and Kurtzman and others, and so some of them were aware of what was going on and how cool it was that Bo, and, by proxy, me, could be there and be working with him. Among my friends, there were a few that were interested in this and were envious, but there were just the few that I knew that were into comics and knew who Eisner was and especially since Warren was by then reprinting the Spirit in his own magazine.

BO: On a side note, the best thing about Will’s class… was Will! The best thing about Kurtzman’s class was all the people he brought in, like Gahan Wilson or a guy with a Robert Crumb Sketchbook!! Harvey also took us to Neal Adam’s Continuity Studio and the studio with Wrightson, Kaluta, Smith and Jones! Wrightson, on our visit, showed us his trash can which contained an original Frankenstein illustration which he had scrapped because he blew a line in the sky while inking. I was horrified. He refused to put white-out on that stuff.

ANDELMAN: Let’s jump ahead. At what point did you start doing work yourself in comics?

SCOTT: I would say that is roughly in the zone of 1981.

ANDELMAN: Okay. So it wasn’t too far off from then.

SCOTT: No. It was shortly after Bo’s time with Will that we went back down south to Columbia where we lived. Bo came back from school, and he was working. I think he was working at like a video store. I am not sure what job I had, but we were both trying when we weren’t doing those things to build up our portfolios to try to get out there and get to work. So come about 1980, 1981, thereabouts, we then moved up to New York. About three weeks into our moving there, I finally took the plunge and made arrangements to meet with a bunch of people, and Bo was going to meet with people the very next week. So I went in, and I got work with a number of houses right off the bat, and I was elated. But then there was more pressure on Bo to get work. Then we went to see Will, and I told Will about how I had gotten work and all this stuff and how happy I was, and he said, “Congratulations, that’s great, but I’m concerned about this guy here,” and he pointed to Bo. He said, “You are the younger brother; I want him to make it, too.” Bo said, “My chance comes up early next week.” But his concern for Bo was, I thought, really very touching, and Bo felt that. I also know that he was doing everything that he could to get his portfolio in shape.

A few days later Bo went in to Marvel and he was supposed to meet me at the train station to go back into New Jersey after say an hour and a half. I was actually dropping off work or picking up a script from somebody, so I was the seasoned professional, and he was going in to try to get some work. I waited for four hours. Finally, he showed up, and he was all smiles, and he had work with Marvel, and with this one, that one, and the other one, and I am going, “That’s great, but you could have called.” But no, he couldn’t, not then, there was nowhere a phone message could have be left, so anyway, I was a bit peeved with him, but I was also super happy that he was able to get work right away as well.

ANDELMAN: What was your first assignment?

SCOTT: That’s a good question, because there were these goofy little things that came before that. In 1979, I got a couple of frontice pieces for a comic that DC was doing called Secrets of Haunted House, and so that might be the very first “assignment” I was ever given, but if you take those odds and ends out of the equation, then the first ongoing thing was probably a script by Todd Klein for a new book that DC was just coming out with called New Talent Showcase. The story was called “Class of 2064.” It was a three-parter, and Todd Klein, as you know, is the premier letterer in comics. Also, he’s a great designer, but he had written this script, and I ended up doing the art on that, so I would say that that was it. I got that job that first day, along with a script from Warren for one of their magazines, which folded shortly thereafter, and it never saw print, thank God. Then also that day, I sold a six-page story to Archie Goodwin at Epic Illustrated. All three of those assignments happened on the same day.

ANDELMAN: Pretty good day.

SCOTT: Yeah. It was a big day for me.

BO: Actually- it is truly great getting the last word here. I got my first job from Joe Orlando at DC Comics for some Witching Hour filler pages in 1978. The date is on the back of the original page!! Aha!! And I got Scott his first pro gig because I had done a story shortly thereafter for Jack Harris (also at DC), who was editing Secrets of the Haunted House. I sent Scott’s samples to him. Scott did a one-pager of Destiny (that was very cool!). I then did one more 5-pager for Jack and tried out for a book called Mr.E – get it? – but but unfortunately, that bastard Dan Spiegle got it. Dan kicked my ass all day in his rendition of the character but of course I had no clue back then. After that Scotty and my days at D.C. “went dark” until ‘82 or ’83 when we ventured once again to NYC and Scott had his big day and I got going again; this time doing stuff for Swamp Thing and Epic and later moon knight. I had inked a lot of Will’s pencils for the joke books he put out through Scholastic and thought I was getting his “line” down. I was thoroughly convinced I had implemented it successfully in my early pro career, but of course, once again I had no clue. I still had some part of that pole to extricate.

ANDELMAN: Over the years, did you guys maintain some contact with Will?

SCOTT: Yes, for a while, whenever I would do a large book I would send him a copy for his files and a copy for him to mark up, and I would ask him, “Please rip me to shreds and tell me how I can make this stuff better.” And I did that with a couple of different books. I would have kept doing it except that at a certain point, I was doing work that was mostly aimed at the commercial market, and I was a little embarrassed to hand it over to Will, because I felt like, well, it was not the kind of stuff he does. He doesn’t do Superman or Batman just to do it or whatever, he does his own work, it is individual, it is independent, and so if I had something that was along those lines, I was more likely to show it to him.

BO: Will saw everything I did because I mailed him everything as I did it, sometimes in Xerox form. He always loved the drawing but took me to task on storytelling and he was dead right. The one time I got an unrestrained, unqualified kudo from him was for a story I did for the 25th anniversary of Heavy Metal that was called “Underworked.” I wrote and drew it with Will’s approach in mind and to this day it’s one of my best efforts. However the note he sent congratulating me with no — I mean no — criticism whatsoever was promptly misplaced and never saw the light of day again. Perhaps I dreamed it, after all.

ANDELMAN: Can you think of anything in particular that you did show him that he commented on?

SCOTT: Yeah. The last thing I sent him was a graphic novel that I did called The Upturned Stone, which was a 64-page ghost story, and it was my own creation. I wrote it and drew it, and so because of that, I felt like it was within the parameters of what I felt he would be comfortable talking with me about, because he knew it meant a lot to me. He sent it back, and he gave me some specific notes about how I needed to reinforce certain bits of information to both the visuals and to the text.

One of the things that he would tell you is, “Don’t assume the reader got it the first time. If it’s important, try to repeat it. Find a way to tell them twice so that they will get it.” He was very conscious of establishing things, both the visual look of the place but also character work. So he gave me those specifics, but he also gave me general notes that would help, as well, and he said that he really looked forward to sitting down with me at some point and just going through it and talking about it, which I would love to have done, but whenever I saw him after that, it was always at a show somewhere.

ANDELMAN: When was the last time you saw him?

SCOTT: It was in San Diego the year before he died. It’s funny, because my friends and I always stay at the same hotel that Eisner stayed at in San Diego, and we would always see him down in the restaurant for breakfast. He would be having a breakfast with some of his French publishers and all that, and we would just say, “Hi,” and we would do our thing. Then the next year, Will wasn’t there, of course, and we all felt very bad that Will wasn’t there. But Bill Stout was in the restaurant, off to the left. He was eating his breakfast. My group was sitting around, and we got Bill’s attention and a couple of other people that we all knew knew Will, and we toasted him, sort of the breakfast club sort of thing.

The last time we saw him was in San Diego. It was funny, because he was doing a signing. He was signing a bunch of posters in a room off the hotel lobby, and we happened to notice him as we were going to the elevators, so we walked in. It was me, George Pratt, John Van Fleet and John Hitchcock. Will was very carefully signing his name to all these posters, and every time he would finish one, the publisher would carefully go and put it over on another table. Well, as Will was getting close to the end, I grabbed up the stack, the huge stack of posters that he had signed, and when the fellow took the last one away, Will pulled his glasses back down and said, “I’m glad that’s done. Man, that was exhausting.” And I said, “But what about these?” And he turned around, and there was this huge stack of posters for him to sign, and you should have seen his face. It was just like, “Oh, no!” We busted out laughing, and we assured him it was a joke and that he didn’t have to sign any more. But he was a great guy for that. He never took himself super seriously. I think that he was very conscious that other people really did admire him so much, so he was always quick to try to put people at ease.

BO: Same here – San Diego. Alex Saviuk, Mark Sparacio and I got a last photo with Will and I did something I rarely do. I hugged him and told him we loved him. He just looked so frail. Denis Kitchen was helping him walk. I knew “See ya later, Will” wasn’t going to cut it this time. I’m so glad I did that.

ANDELMAN: Have you ever deliberately worked Will into your work?

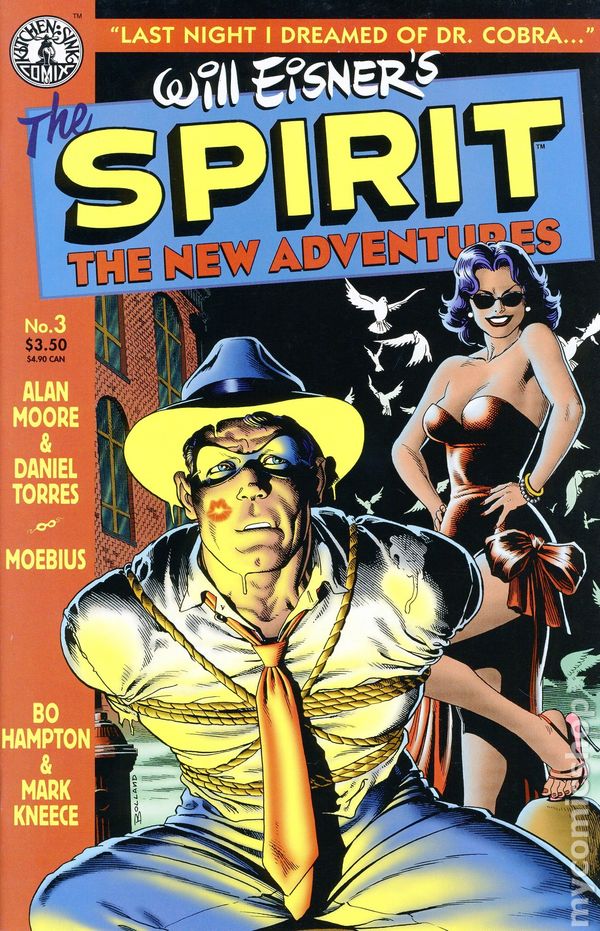

SCOTT: Well, first of all, let me say that I did a Spirit story.

ANDELMAN: Oh, you did?

SCOTT: Yeah. I did a story for The Spirit, The New Adventures that Kitchen Sink put out. It was everybody’s chance to tip the hat to the master. Mark Kneece and I co-wrote this story called “Baby Eichbergh,” telling the story of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping with a happy ending, and the Spirit solved the case. It was one of the most enjoyable projects I ever worked on. It was about 16 pages, something like that. So I actually did get to do the Spirit, to draw and paint the Spirit, which was, let me tell you, a kick.

There is one other funny little thing I will mention, and that is that Will was in the very best of shape for someone his age up until the day he died, and he did that partly by being an avid tennis player.

Bo and I did spend time with him, but at one point, my brother Toby also met Will. He and Bo ended up playing doubles tennis with Will and one of Will’s buddies. Oddly enough, Bo is currently the best tennis player in the family because he has kept doing it ever since, and I stopped doing it a long time ago. Toby, at one point, was probably the best player in our family, and at one point, I had that crown. But at the time, Toby was very good; Bo wasn’t. These two older guys mopped the floor with these two young punks, and they weren’t very gracious about it. They were, “Ha, ha, we kicked your ass,” that kind of thing.

So Toby, who by this time knew how Will’s humor worked and he knew he could say this, said, “Okay, old man, let’s do it, you and me.”

And Toby pretty much took him to school.

Will was old school when it came to humor. He could dish it out, but he could take it, too. So when this young punk was running him around the court and using drop shots to make him run even more, he got quite a workout from Toby. And when Toby was goading him, he took it with grace. That was the thing. It’s like he was absolutely assured of his place in the world.

He knew that he was a huge influence. People really are not bullshitting when they say that Will was probably the most influential guy who has ever worked in this field. When Alan Moore and others commend Will as a writer, I don’t think they are lying, they are telling it like it is. I mean, he essentially made everyone understand that this form is a lot more than you think. He stretched it much more than anyone else. I think that there are things that he did that were so sophisticated they haven’t been surpassed since. So yeah, I think he knew his value on the Earth and that when somebody like Toby was better at tennis than he was, it was no big deal. He could take a joke, and he could take the fact that he wasn’t that great at that, because he knew that he was a much better cartoonist than any one of us was going to be.

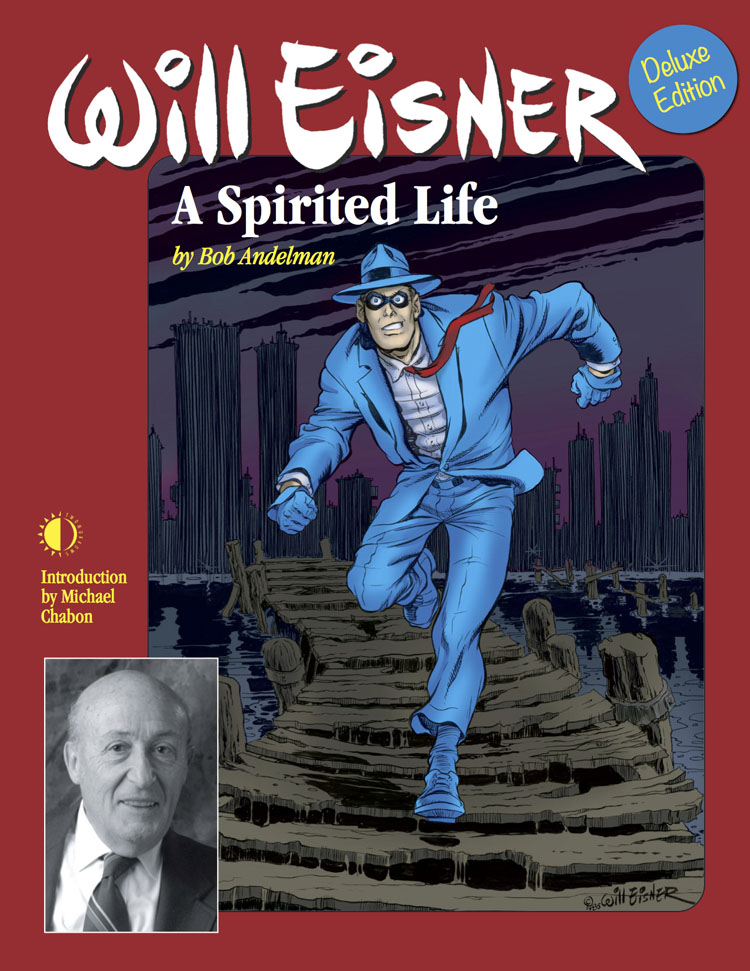

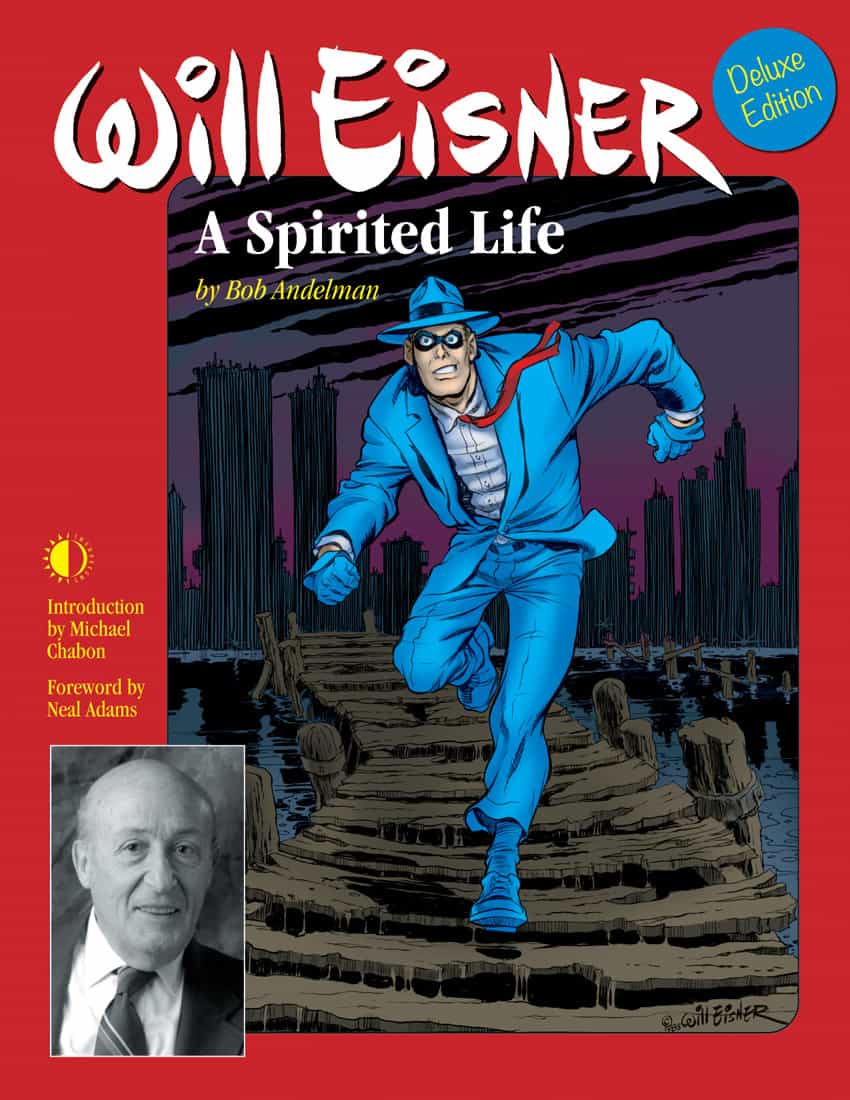

Order Will Eisner: A Spirited Life (2nd Edition) by Bob Andelman, available from Amazon.com by clicking on the book cover above!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!